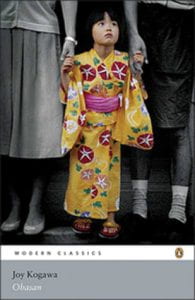

Obasan, written by Joy Kogawa, is an insightful novel into the horrors the Canadian-Japanese experienced during the Second World War, and how the history still shapes many of their lives years later.

The story follows Megumi Naomi Nakane, who as a young girl experiences the internment of the Japanese-Canadians first hand and how she grew up throughout such a harsh period of time. The story is told through a handful of Naomi’s perspectives starting the story off in 1972 with her uncle Isamu. Her uncle soon passes away and Naomi drives out to visit her Obasan (aunt/uncle’s wife). After a few chapters with Obasan the story then transitions to being told through a series of old letters and flashbacks. It is here where we are given the full story from Naomi’s perspective piece by piece until we return to the 70s for the final few chapters, still pondering the past events.

Though an important perspective and a powerful story, the novel can feel very run-on and unnecessary at times especially during the first half of the book. This is due to the writing style which the author has chosen to use. Throughout the story Kogawa writes in extreme and precise detail, outlining every aspect of the scene she’s describing. While useful for laying down exactly what the author wants the reader to know and picture, Kogawa tends to do this somewhat erratically, choosing to focus on some of the most mundane or insignificant aspects of a scene. This can be anything from a full page exclusively about the clutter of a kitchen fridge, to the patterning on a set of dishes used once in a single chapter. While one could look at this from a literary standpoint and say it shows the contrast of different ways Naomi and her family lived throughout the years, this unique usage of description can turn a reader away from the story due to how frustratingly time consuming it can be. The novel can feel slow and verge on boring thanks to Kogawa’s writing, which can be quite bothersome when trying to read a novel that tackles such a complex and painful subject. The use of flashbacks can also feel rather jarring at times, due to not always being certain as to where and when an event is taking place unless explicitly stated (which it often is fortunately). However, I did find that the impact certain points or ideas had would not be felt the same if the story were to be told in a linear fashion.

Though a tough read at times due to the author’s methodology, Obasan is an important story working to understand about how to live with oneself after an atrocity like the internment camps during WWII. In the end, I enjoyed this book, even if it isn’t for everyone. I would recommend it to any and all looking for a historical-fiction that delves deep into the personal and emotional aspects of how war changes even those not directly involved in it.

-Image links-

https://www.project44.ca/japanese-canadian-internment

https://fvcurrent.com/p/tashme-museum/